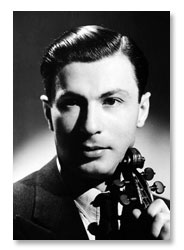

Milstein, like Elman, Zimbalist, Seidel and Heifetz, was one of the great Russian-Jewish players of the Böhm-Joachim-Auer line. His recollection of studying with Auer highlights once again the master’s insistence upon individuality which Milstein took to heart: ‘If you asked him […] about the playing of a certain passage, he would say, “Go away and think it out for yourself”’. Apart from this he did not accredit much of his success to his teachers, but rather enjoyed the healthy competition of sharing a class with rising stars such as Heifetz, Hansen and Seidel. When the Russian Revolution forced Auer to emigrate Milstein was already well equipped for international prominence.

At this time he was engaged by the Ministry of Education to give concerts around Odessa. A few years later he met Vladimir Horowitz and began giving concerts with him in Kiev, Moscow and other cities. Anatoly Lunacharsky, Commissar of Fine Arts and Education, reviewed them under the heading ‘Children of the Soviet Revolution’; this kind of publicity led to many more concerts and a handsome income, which the duo gave to beggars as they had ‘nothing to spend it on’. Because of their potential as ambassadors for Soviet cultural education Milstein and Horowitz were allowed to leave Russia for a European tour. Szigeti advised a demurring Milstein that Europe was agog for such artists as himself and, finding this to be true despite the already-established popularity of his older compatriots, Milstein never returned to Russia.

At his US début in 1929 Milstein (under Stokowski) presented Glazunov’s Violin Concerto, which he had played under the composer’s baton at the end of his studentship in Odessa. This secured his ranking in America alongside Elman et al. and he later took US citizenship, renouncing affiliations to Soviet politics and the Communist party.

There were certain trademarks to Milstein’s playing. He was utterly attached to his fiddle (even placing it on a chair nearby whilst shaving!) and almost equally obsessed with nurturing his own individualistic style. He held the violin very high without a shoulder-rest and bowed mainly from the shoulder. He employed position changes and vibrato for expressive purposes in the manner of the Germanic pedagogic line to which he belonged, allowing more non-vibrato than most of his contemporaries. Cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, with whom Milstein and Horowitz played trios, claimed that his friend was at his best in unaccompanied repertoire when he did not have to collaborate with another musical personality. There are accounts of tension between Milstein and conductors, although his recorded output includes plenty of concerto performances.

Reflecting the stature of an artist as important as Milstein through a small selection of recordings is a tall order: like many of his generation he recorded very widely over a long career and his work is still both famous and highly regarded by performers and listeners. Comparison with Heifetz, not least because of his similar background as one of the many great Auer pupils, is perhaps inevitable. In technical security he is almost Heifetz’s equal and there is a toughness and almost laconic invulnerability to his playing on record that could equally apply to Heifetz. That his performances, such as a fine recording of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in 1955, sound so normal to our modern ears perhaps demonstrates more than anything else that he belonged to the illustrious band of superstar players who defined this style—a powerful tone with a silvery yet clearly-projected high-register sound, a sonorous and yet slightly metallic G-string colour, and a richly developed vibrato—aspects we still expect to hear from a virtuoso concerto violinist today.

This is not to say that Milstein’s playing is not stylistically interesting. His 1951 performance of Brahms’s Double Concerto with Gregor Piatigorsky may refrain from some of the characterful traits of earlier renditions but is nonetheless extremely powerful and virile, whilst his 1949 Glazunov Concerto and, indeed, his 1940 recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto show charisma and depth. The Glazunov is not perfect, with some sharp G-string tuning in the finale, but the bitter-sweet control and avoidance of sentimental excess in the earlier movements complement this romantic yet slightly brittle work to great effect. The 1940 Tchaikovsky selected here is rather better than, for example, his 1953 recording with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Charles Munch (which evidences some slightly scratchy sound in the first movement) and is more flexible in general, even though it studiously avoids the (by then) unfashionable portamento.

In chamber repertoire Milstein suffers a little from the ‘big sound’ problem of his generation of concert-hall concerto artists (a branch of the profession that probably reached its zenith in Milstein’s heyday and has become rather less common in recent decades). Thus his Prokofiev Op. 94b Sonata, recorded in 1955 with Artur Balsam, is over-projected and lacks sensitivity, nuance and psychological depth: Milstein sounds oddly ill-at-ease even in this relatively large-scale work. Equally, his many unaccompanied Bach recordings sound over-blown nowadays: his 1956 D minor Chaconne, for example, has all the technical polish one could wish for but is articulated in a style that makes no concession whatsoever to the repertoire, with a steely strength, big tone and hardly any rhythmic nuance, quadruple-stop chords being snatched rather brutally in a manner similar to that of Joseph Fuchs.

Milstein’s collaborations with Vladimir Horowitz, however, inject a spark to a number of chamber recordings, and these—including a charismatic and purposeful performance of Brahms’s Violin Sonata, Op. 108 from 1950—are perhaps his most successful. Taken overall, Milstein can be seen as nothing less than one of the great performance phenomena of the twentieth century.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Milsom (A–Z of String Players, Naxos 8.558081-84)